Figure 1:

Pictures of Dr. Robert Earl Lee (October 9, 1906-August 21, 1997), author of Blackbeard the Pirate: A Reappraisal of His

Life and Times. Left: graduation from Wake Forest Law School in 1928 and,

Right: Memorial from the Campbell Lawyer,

Summer 1997.

For Lee, Americans, and especially North Carolinians, were absolutely innocent in the development of piracy – England alone was the nemesis responsible for that derogatory reputation, as he saw it. This was certainly not true. England provided the initial drive towards piracy, but all Americans alike reveled in it, especially the West Indies, both Carolinas and their sister colony of the Bahamas. Americans refined piracy through the centuries, and made it work far better than the English had ever dreamed. By the eighteenth century, piracy in America had become rather unique and essential – and quite different from newer British Whig or progressive economic policies.

Lee misses the historical context of the times, almost 300 years removed from when he taught law at Wake Forest and Campbell University. He recognizes bias well enough to observe its effects in modern contracts, but does he understand bias when translated from the colonial period – in a backwater wilderness devoid of any sense of European civilization or law? Does he recognize the inequality of the colonial period that elevated the wealthy landed aristocracy and essentially excluded the majority of the population? Furthermore, does he understand the differences between European civilation and the wild and remote nascent civilization forming on the American frontier?

Lee misunderstands the genesis of the records he researches. When Lee refers to the “people” of North Carolina being “mutinous,” he denotes the wealthy administrators who were arguably pirates themselves, not the people in the fields tending their hogs and trading their meager produce for necessaries in the local towns. The majority of the people are ignored by traditional documentary sources. He said that the “people” were “so used to disposing of their governors that they assumed they had the right to do so.”[2] Again, he only spoke of those few recorded in the records, an easy mistake to make, assuredly.

These were the men of whom Lee speaks glowingly in the following pages: Gov. Charles Eden and his council, Edward Moseley, Maurice Moore, the Ormonds who “played a prominent role in the history of Bath Town and Beaufort County,” Thomas Pollock, Tobias Knight, and many others.[3] Some of these men opposed Blackbeard.[4] Some, like the Ormonds, probably never even met the pirate. Still, all of them were ultimately concerned with their personal fortunes, regardless of from where it came. The unmentionables, like the greater number of commoners, today’s 99%, rejoiced in Blackbeard’s visits. Edward Moseley and Maurice Moore, specifically, founded the Lower Cape Fear settlement of Brunswick Town and stole as much as a hundred and fifty thousand acres belonging to the king while cutting others out of their monopoly. Their “Family” has been compared with a “syndicate,” much like the Gambino organized crime family or their perhaps less organized counterparts, or pirates. Again, “rovers of the sea” and “rovers of the land” differ in mode of travel only. The “people” of North Carolina are still subjects of these hierarchical forces of inequality that “belied the seeming equality of a poor state,” as historian Paul D. Escott infers.[5] The rest of America, it seems, contracted the same conservative illness.

And lastly, Robert E. Lee assumes Johnson-Mist to be an accurate source for the information that he obtained on Blackbeard, even touting the legends of his fourteen marriages and the prostitution of his wife, supported by no primary sources whatsoever. Then again, Lee believed like so many that he could trace his own ancestry back to the “notorious” pirate of legend. Why anyone would wish to be related to such a vile and wicked pirate as Johnson-Mist’s star antagonist is beyond comprehension!

Lee’s historical work has to be scrutinized carefully to avoid these amateurish mistakes. An expert in the law does not an expert in history make. He says that “because of its isolation and thinly scattered population, the troubles incident to colonial piracy were delayed in reaching North Carolina.”[6] For this, he thinks that the colony’s association with piracy came only when piracy was at its worst and, therefore, its reputation unduly suffered. Lee also says “caught in the undertow of piracy and undeterred by government, North Carolina’s colonists, in 1718, could hardly have been expected to resign a profitable connection with the pirates.’”[7] The piratical anti-government theme, like Charles Vane’s at Nassau, is palpable throughout Lee’s book, obviously influenced by the same conservative ideology that created the “Flying Gang” on the Bahama Islands.[8]

This is why professional training in the historical arts is essential. A professional historian spends his life studying the past, not just his short twilight years near retirement from his life-long expertise as a lawyer, journalist, or politician. North Carolinians’ and other Americans’ tendency toward treating history as a hobby handicaps its proper study and understanding. Historians train for years to think as their subjects do. For example, to understand the colonial era, you have to study intently that era and learn to think like a colonial, including the various classes of people from colonial culture. You have to study the needs and stamina of a cultural framework quite different from your own. Historians must be part sociologists, anthropologists, and psychologists, as well as historians. No professional historian would dare practice law like Lee, perform surgeries like Dr. Hugh Williamson, or preach like Francis Lister Hawks. Still, it did not prevent them all from writing amateur history and claiming to be historians.

North Carolina’s association with pirates began when the charter had been issued to the Lords Proprietors in 1663. It probably began even before that date, although association with the wealthy, careless, and distant proprietors certainly enhanced its piratical reputation. South Carolina’s relationship certainly began in 1671 when West Indians came to establish a colony for producing food for their Caribbean island enterprises. No, Carolina was not an end unto itself when it began. It was merely an ancillary operation. The proprietors viewed it as such, which may have largely contributed to its neglect. Again, profit was their only real consideration, not its settlers. Lee’s “people,” the actors of whom he considers worthy of note, were the only voices that ever mattered to him or to the proprietors.

The actual people whom Lee completely ignores merely enjoyed better prices brought by pirates and their fences. They had to resort to illegal merchandise to make ends meet in an unequal world that never really belonged to them. The then-affordable sugar and cocoa landed on the docks for the landless to purchase and load their wagons and head home to their tenantcy to feed chickens and make their family cups of sweetened hot cocoa to ward off the winter chill. Moreover, they usually did not participate in elections because the franchise was tied directly to freeholds, or land ownership. The vote belonged only to the wealthy.

The North Carolinians that we can read about in vital records actually welcomed pirates in 1718, as much as it did when part of Henry Avery’s crew settled in the Albemarle. Indeed, Lt. Gov. Spotswood of Virginia, after successfully capturing Blackbeard’s crew and killing him, faced derision from his fellow Virginians. As will be shown, some North Carolina residents (those few that appeared in the usual records) were pirates or related to pirates themselves, like the Jamaican assemblymen who profited greatly from the practice. Again, these were not the poor and landless living in the documentary background.

South Carolina favored business with their pirate brothers before the extravagances of 1716-1717, but not so much since Stede Bonnet, Edward Thache, and Charles Vane blockaded their primary harbor, took their ships, held their substantial citizens (Lee’s version of “the people”) prisoner, and invaded their town. This personal affront served to temporarily quell their love and maintenance of piracy – it helped to end Blackbeard’s career. Furthermore, economics had a large part to play. Arne Bialuschewski approaches the best explanation for the two Carolinas and their disparate attitudes toward piracy:

The Carolinas provide a good example of colonial settlements where the attitude towards pirates underwent a complete change in the early eighteenth century. For years the inhabitants, far away from any sources of military support, lived in fear of attacks by Native Americans and the Spaniards. Furthermore, prior to the development of rice cultivation in South Carolina in the late seventeenth century, the colonies lacked a major export staple capable of bringing prosperity to the region. Under these circumstances pirates were welcomed by the inhabitants for both their military value and the trade they offered the sparsely populated Carolinas. As in other colonies, the main benefit of the pirate trade was that it allowed access to looted specie and merchandise at discount prices. In the early eighteenth century, however, South Carolina began to flourish in its own right, as rice exports brought wealth to the colony. When pirates appeared off Charles Town in 1718, the source of prosperity was endangered. Piracy not only threatened local shipping but also raised indirect costs such as insurance, commission fees, wages and interest rates at a time when the economy was recovering from a costly war against the Yemassee. North Carolina, by contrast, lacked a major staple and the economy remained depressed after the war, so its mercantile and political elite continued to deal with pirates.[9]This is not to diminish the distinguished law career or the massive amount of research that Lee performed for his book on Blackbeard. He explored every available piece of primary evidence, even listed them in an appendix. Still, he was led astray by the plethora of legends associated with Blackbeard, as many of us have been and still are. He occasionally delved into and seriously explored the wild assumptions of “a cousin of my uncle on my mother’s side.” These sorts of fascinating bedtime stories rarely provide serious evidence. Sometimes, rarely, those fascinating tales are somewhat reminiscent of the truth, but should never be taken wholly at face value, especially when the desire is to somehow be connected to the infamous figure of a notorious pirate! One must, indeed, consider all forms of possible bias...

----------------------------------------

Update (11/29/2015): The journal copies are limited and running out, but NC Publications has re-released my article as a separate pamphlet titled Blackbeard Reconsidered: Mist's Piracy, Thache's Genealogy and it is available online as well as in various NC museums and historic sites.

Read more about the family of Edward "Blackbeard" Thache and the world in which he lived in the book Quest for Blackbeard: The True Story of Edward Thache and His World, to be released around Christmas of 2015.

Get the poster of Blackbeard's family history and other gift ideas at this address:

http://www.zazzle.com/quest4blackbeard

------------------------------

How did the QAR wreck at Beaufort Inlet, North Carolina? Many have claimed that Blackbeard wrecked his ship on purpose. This may not be true... you judge.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rHz9-uEJRb0

How did the QAR wreck at Beaufort Inlet, North Carolina? Many have claimed that Blackbeard wrecked his ship on purpose. This may not be true... you judge.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rHz9-uEJRb0

------------------------------

Warning!! This could change your most basic perceptions...

Warning!! This could change your most basic perceptions...See how the Bahamas and its sister colony Carolina became pirate strongholds through neglect of its wealthy private owners years before Hornigold and Thache and their “Flying Gang” - how pirates came to the American South, killed 600,000 people to maintain their "peculiar" institution of slavery, and developed a unique conservative ideology that survives today.

See where America began – from New Providence and Charleston to the Lower Cape Fear - enmeshed in the violent wilderness “beyond the lines of amity” – competition and sport, stealing treasure and burning ships - with Caribbean Buccaneers and Pirates of the Golden Age!

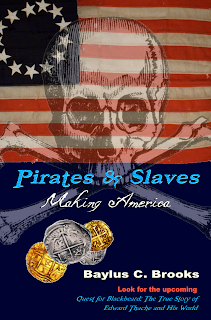

http://www.lulu.com/shop/baylus-c-brooks/pirates-slaves-making-america/paperback/product-22351221.html