-------------------------------------

Excising the many remaining pirates [in early 1718] proved difficult for Woods Rogers because of many smaller islands that “are not worth while to the Government, either to setle them, or be at any expence at all about them, for such smal Islands can never maintain a sufficient number of people.”[1] Still, they would prove useful to pirates on the run, endeavoring to remain hidden from his majesty’s forces. So did the myriad of tiny islands with their shallow “shoal traps” of the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Thache, of course, briefly sojourns upon the new and remote port of Bath Town on the Pamlico River, displayed in figure 1, where Governor Charles Eden then lived.

The older records, newspaper and government accounts, especially the North Carolina Colonial Record Collection, have proven bleak to the task of studying pirates. Thache allegedly enjoyed his congenial and beneficial relationship with Gov. Eden, as the Jamaican privateers with governors Archibald Hamilton and Peter Heywood, and assemblymen Daniel Axtell, Jasper Ashworth, and Lewis Galdy. From his new Carolina haunts, he raided vessels all along the eastern seaboard, blockaded Charles Town, took prisoners, and destroyed ships and their cargos. He became an “official” menace that relied on the politically-weak private colony of North Carolina, never much a favorite of Lt. Gov. Spotswood in Virginia, who took particular interest in Thache in the latter part of 1718.

Figure 1: Portion of Edward Moseley’s Map of 1708 showing the location of Bath Town (top) and a redrawn map of John Lawson’s plan for Bath Town from 1807 (bottom) – Source: Lambeth Palace Library : Treasures from the Collection of the Archbishops of Canterbury (London: Scala Publishers Ltd., 2010), 138-9; Richard John Forbes, James R. Hoyle, and Robert R. Bonner, “Plan of the Town of Bath Beaufort County State of North Carolina” (1905), from North Carolina Maps [online], http://www2.lib.unc.edu/dc/ncmaps/ (accessed: 23 August 2014).

In August, the Virginian governor wrote the Board in one of his many long letters, that:

The Proclamation prohibiting the unlawfull concourse of persons who have been guilty of piracy was occasioned by the great resort to this Colony, of certain pyrates who being cast away in North Carolina, surrendered there upon H.M. Proclamation; but as there’s no great faith to be given to the forc’d submission of men of those principles, it seem’d necessary in a country so thinly inhabited as this is, to restrain their carrying arms, or associating in too great numbers, lest they should seize upon some vessel and betake themselves again to their old trade as soon as their money was spent.[2]

Spotswood, following a long line of Virginian officials and statesmen, never cared much for North Carolinians.

Rediker reminded that these were the peak years for piracy, with 70% of captures occurring between 1718 and 1722. Thache, erroneously alleged to have purposely scuttled the QAR, erroneously alleged to have marooned his crew in North Carolina, continued trading stolen goods with Bath residents, and flirted with the two more imposing governments of South Carolina and Virginia. Blackbeard had entered the pages of recorded history just over a year before Lt. Robert Maynard, sent by Spotswood, killed him at Ocracoke. His was a short career, much maligned after his death. Afterward, Rediker’s “Golden Age” began to end in 1722 and finally did by 1726. The new age of the debasement of pirates like Blackbeard began and would continue for the next three hundred years. Planting sugar would have been safer to posterity than becoming the stuff of legend.[3]

A scant percentage of Rediker’s estimated 2,500 pirates were actually executed. The elite leaders retired with their great wealth, having accepted pardon. Their crews, however, disappeared into the undocumented crowds of merchants and farmers. Lindley Butler intuitively ascertained that thousands of pirates could not just disappear without “blending into the yeoman farmer and fishing communities.”[4] Marcus Rediker, after reading A General History, reflected upon John Rose Archer, who once sailed with Thache in 1718, and later “tried to avoid the gallows by lying low, working in the Newfoundland fisheries.”[5] Pirates simply found new vocations.

The fact that pirates routinely used the inland waterways and shallow sounds of North Carolina’s Outer Banks cannot easily be disputed. Here, they probably found a home and North Carolinians today tend to embrace their pirate heritage. The introductory article written by Jane Stubbs Bailey, Allen Hart Norris, and John H. Oden, III for the Beaufort County Deed Book I included the reminiscences of a descendant from a “contemporary of Black Beard.”[6] The informant said:

We are descended from those wild fellows. The folks in North Carolina lived by the goodness of the pirates and many claim ancestry to them. Those “sea dogs” were the bringers of goods to a poor, very isolated part of the world. When Black Beard’s reign of tyranny was near an end, he told a group of his young pirates “to disperse and lose themselves among the fields, and woods, and people, to marry among the people and survive, for those that stayed with him would surely die with him.”[7]Reminiscences of Blackbeard’s legend are common. The genealogists’ analysis of the deed records was fairly sound, especially concerning James Robbins and Edward Salter. Both men were associated with Thache and both left wills that revealed more than the average estates. These details are not in question – only the connections to Thache himself. A great deal of actual history has been confused thanks to telling, retelling, and modifying these legends over the centuries. Most of the damage truly occurred since the early twentieth century amidst the commercialization of Eastern North Carolina. This book evolved from a strong desire to clear the biased smoke and remove the deflecting mirrors of these legends.

Salter particularly possessed great wealth and prominence in the colony of North Carolina. Salter appears in Bath deed records in September 1721, just three years following Thache’s death. He married in Bath and had two children. In only a few years, Salter, a cooper, paid £600 for the 400 acre plantation on the west side of Bath Town Creek once owned by Governor Eden. He later purchased numerous plots west of Bath on the Pamlico from the estate of Lewis Duvall totaling 3,371 acres for £450. At one time, he even owned a portion of the future town of Washington, North Carolina’s prominent seaport on the Pamlico and the seat of John Gray Blount’s business enterprises. He cultivated family connections to the noteworthy families of the state: Bonners, Porters, Harveys, Gales, Swanns, and Blounts. Salter, in his last will and testament, appoints his “well beloved friend, Colonel Edward Moseley,” one of the executors to his estate.[8] Past North Carolina redeemer historians have asserted that Family-member Moseley, with “scholarly cultivation and refinement” was “long-time speaker of the General Assembly and perhaps the colony's finest citizen.”[9] As noted earlier, Moseley was no more than a wealthy land profiteer, placed on a pedestal by ex-Confederate North Carolina redeemer historians since the Civil War. From such humble beginnings as a captured cooper from Henry Bostock’s crew, Salter had joined the “1%,” North Carolina’s elite population.[10]

Other pirates desired anonymity. They came to the mainland and became planters, fisherman, mill workers, anything to “escape the gallows,” as Butler and Rediker phrased it.[11] Most pirates never attained the lofty societal position of Edward Salter. Only a handful, like Robbins and Salter, became North Carolina’s budding aristocracy after Thache’s demise.

Until 1729, North Carolina was privately owned and susceptible to abuse and corruption and, after that time, royal government leadership made for a relatively more certain life in the colony. The new “privateers” of America could be more certain of their profits. This is even truer after the American Revolution.[12]

Upon arrival back at Bath Town, having the Adventure condemned in a sham court, and accepting Gov. Eden’s pardon, Johnson-Mist told the world that Thache married to the young girl, about sixteen, and that the governor performed the ceremony:

… this, I have been informed, made Teach’s fourteenth Wife, whereof, about a dozen might be still living. His Behaviour in this State, was something extraordinary; for, while his Sloop lay in Okerecock Inlet, and he ashore at a Plantation, where his Wife lived, with whom after he had lain all Night, it was his Custom to invite five or six of his brutal Companions to come ashore, and he would force her to prostitute her self to them all, one after another, before his Face.[13]

Johnson-Mist, on the point of Blackbeard’s marriges, was brutal to Edward Thache. Even after A General History, the legend grew wilder and less controllable. The marriage legend to the Ormond girl was highly improbable after an in-depth study of the Ormond family history related to North Carolina. It should have been obvious especially to Ormond descendents, but many craved the infamy of a connection to the bloody deeds of Johnson-Mist’s “Blackbeard the Pirate.” Furthermore, nothing in the actual accounts of Edward Thache’s behavior suggest that he was overly “familiar” with as many women as Johnson gave him credit for, or any women for that matter. Johnson simply assumed; he wished his readers would do the same. Then again, life on Jamaica was apparently much more forgiving than any other Anglican outpost, as the records for Thache’s brother Cox attests. For mariners and residents of port towns, there were plenty of opportunities to find and enjoy “marital bliss” without the associated paperwork.

While Cox Thache essentially “married” Jane, a slave of William Tyndall/Tindale, nothing in the Church of England records suggests anything other than a fair, if short, relationship. Then again, these records are brief notes of special moments in daily lives. They tell almost nothing about the relationship. The church could not solemnize such a marriage and, for the marriage itself, there is no record, but they faithfully recorded the children christened from it, with both parents named by the church, perhaps for legal reasons. Cox had perhaps three children by her, maybe more; one child named after his mother, Lucretia, the record shown in figure 2.[14] Jane also received her freedom afterward, though she probably did not stay with Cox after he went back to his home plantation in St. Catherine’s, presumably to care for his mother and look after the family estate. “Jane Teach” apparently died a “free Negro woman” on April 10, 1787 and was buried no doubt in the “Negro Burying Ground” located on the west side of Kingston and shown in figure 3 below.

Presumably, Cox’s sister Rachel married. Still, no record of that has been located. She may also have died, as death was quite common in the early eighteenth century and especially in the presence of tropical diseases. Cox’s “Loving Brother” Thomas was alive in 1736, as the will attests, but his whereabouts are unknown. Still, there were other locations still accepting of pirates and their families.

Figure 2: Baptism of Lucretia Teach, daughter of Cox Teach, in 1746 at the age of twenty-four – Source: "Jamaica Church of England Parish Register Transcripts, 1664-1880," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/VH64-5ND : accessed 01 Nov 2014), Lucretia Teach, 02 Jan 1746, Christening; citing p. 90, Kingston, Jamaica, Registrar General's Department, Spanish Town; FHL microfilm 1291763.

Figure 3: “Negro Burying Ground” on map of Kingston, Jamaica - Source: Hay's City Plan Map of Kingston, Jamaica (1745)

Mrs. Ellen Goode Watson Winslow assures that the first tax list found in Perquimans County, North Carolina allegedly taken by Edward Hall in 1729, shows several possible recent arrivals and the acreage that they owned. Some of them were named “Thach” or “Thatch.” Thomas Thatch, 96 acres, Spencer Thach, 100 acres, Leven Thach, 72.5 acres, and Joseph Thach, 100 acres were enumerated on this list. Others were Pratts: Zebulon Pratt, 46 acres and Mary Pratt, 33½ acres.[15]

Mrs. Ellen Goode Winslow, the compiler of History of Perquimans County attested to the fact that Blackbeard’s descendants had once lived there. She wrote “It is a fact, however, that two of his sons lived apparently in this county and conveyed property in Perquimans.”[16] She recorded these Thatch/Thach names in her book. Mrs. Winslow also bought into the Virginia origin theory of Thomas Upshur and reported on a local legend associated with it:

He was an Englishman by birth and first settled in Virginia where he married a lady of quality in Alexandria of said state. He soon after began to show his brutal character and was known to have kicked this sweet lady down the stair of their home when in a white rage.[17]

Mrs. Winslow undoubtedly relied upon common flights of literary fantasy to fill the gaps on Blackbeard’s history. She had plenty of company. Perhaps she did so to explain Thatch/Thach records that she compiled for her book, including the reputed 1729 tax list. The North Carolina State Archives also holds several wills and estates of people by that name from Perquimans County, just south of the Dismal Swamp in the Albemarle, on the border between Chowan and Perquimans Counties. Green Thach, Leaven Thach, and Thomas Thach are just a few early examples. These records appear in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth, and include a generation removed from the early Thaches presumed by Mrs. Winslow. These Thaches lived just east of Edenton, on the east branch of Yeopim River that today beomes “Burnt Mill Creek,” or what was then called “Pratt’s Mill Swamp,” which owed its name to miller Jeremiah Pratt (see map in figure 4).[18]

The tax list of 1729, also, has long been called into question, which handicaps the family history of the Thaches. This error must first be rectified before continuing. Winslow first mentions Edward Hall (apart from the tax list) as living on Bentley’s Creek in 1757 in Perquimans County near Henry Hall, William Long, and Edward Willson. A will for an Edward Hall of Perquimans, son of Henry Hall (d. 1774), with wife Rachel and sons Henry, Edward, James, William, and Miles probated January 28, 1788. His father Henry has the oldest “Hall” will record, probated in 1774. Edward himself appears on a 1754 tax record and his second eldest son, Edward Jr. married Elizabeth Moore in 1782. Again, the earliest known Edward Hall in Perquimans County, while possibly alive in 1729, seems more of a latter eighteenth-century figure. Halls (Daniel and William) and Joseph and Rachel Barrow (later neighbors of Pratts and Thaches) are indicated as early as 1718, 1719, and 1720 on poll tax lists – no Thaches, by the way. Jeremiah Pratt appeared by 1720 while John Thach first appears in Chowan County in 1741. Edward Hall may have existed in 1729, but records for this man do not exist prior to 1754. Furthermore, searches for this tax list in Perquimans County and at the North Carolina State Archives are fruitless. Mrs. Winslow may have simply misinterpreted the date of this tax list or it may have been a misprint.[19]

John Thach of Chowan and Perquimans, first emerges on a Chowan County deed record as a witness in 1741. He appears often in Chowan court records, primarily in suits and petitions involving executors of estates and as a member of several juries. Those records show that he was appointed guardian to Hardy and Thomas Holliday Hutson, young orphans of Thomas Holliday, recently deceased. Holliday came from James City County of Virginia (location of Williamsburg) and John may have known him from there before his arrival in Chowan. John “Thack” is mentioned as having a daughter Mildred born before 1744 (probably married Job Mathias/Mathews, orphaned son of John Mathias/Mathews, d. 1746, and Elizabeth Pratt, daughter of Jeremiah Pratt who owned a mill once known as “Pratt’s Mill” where they lived then in “Pratt’s Mill Swamp” in Perquimans County. Pratt’s land was once back of a place called “Sturgeon’s point.”). John Mathias/Mathews’ father, George Mathews, d. ca 1700, owned property there as early as 1696. John and “Mildred Thach” appear as witnesses on a deed in 1747. This Mildred is probably older and may have been his first wife, who gave him Green, Mary, Mildred, and perhaps [H]Esther Thach Boush, wife of James, before his second marriage to Sarah Standin in 1748. Their first child is perhaps Sarah Thach Lawrence, listed in his estate records. [20]

On February 25, 1758, John purchased 500 acres of land in neighboring Perquimans County from Edenton Innkeeper Martha Ann Kippen, the widow of Walter Kippen. This land (approximate location given in figure 4) sat on the east side of Pratt’s Mill Swamp, on a branch of Yeopim River, “beginning on the upper side of the Horsepen branch and running with the mill branch [“Indian Creek” or today’s Bethel Creek] 20 poles above Peter Ponds [Jones].” This is near the modern community of Bethel. His eldest son Green “Thatch” later purchased another hundred acres in Perquimans from Jacob Hall, land formerly patented to Samuel Hall in 1719.[21]

Figure 4: Perquiman’s County location of Yeopim Chapel (1732) and old Pratt’s Mill on former lands of Jeremiah Pratt at Pratt’s Mill Swamp in Sturgeon’s Point - Source: Moseley Map (#MC0017), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA (Annotated by Baylus C. Brooks); Perquimans County GIS, http://perqimanscountygis.com; Exum Newby, “A Map of The Roads and Country Between Edenton and Norfolk with the Dismal Swamp and Great Park Canals etc.” (1845) and J. E. Lapham and W. S. Lyman, “Soil map, North Carolina, Pasquotank and Perquimans Counties sheet” (1905), North Carolina State Archives.

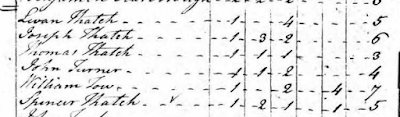

John Thach’s Perquimans County estate record, shown in figure 5, shows his ten heirs, including Green and Thomas, the same propagation of male family names in the alleged 1729 Tax List. Green Thach’s sons were Spencer, Joseph, and Leaven. Together with John’s much younger son Thomas, this completes the alleged tax list that Mrs. Winslow claimed was taken by Edward Hall in 1729. “Edward Hall Senr.,” who probably was the man responsible for the tax list, and Green Thach appear simultaneously on a Perquiman’s County summons dated January 12, 1780, seen in figure 6. Interestingly, the first U.S. Census in 1790, shown in figure 7, contains the same Thach names as Mrs. Winslow claimed on her 1729 Tax List: Leven, Joseph, Thomas, and Spencer. This census even shows Mary and Zebulon Pratt. Winslow’s 1729 tax list was likely dated closer to 1779 or 1789. Still, the specific acreage data that she gave on that alleged tax list do not appear on any other known list.[22]

Figure 5: Settlement of Estate for John Thach of Perquiman’s County, North Carolina (1780) - Source: "North Carolina, Estate Files, 1663-1979," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/QJ8L-1LTM : accessed 31 Aug 2014), John Thach; citing Perquimans County, North Carolina, United States, State Archives, Raleigh; FHL microfilm 002022117.

Figure 6: Portion of Perquimans County Summons wherein appears “Edward Hall Senr.,” who supposedly took the 1729 Tax List mentioned by Mrs. Ellen Goode Winslow in her History of Perquimans County. The name “Green Thach” also appears directly below Hall’s. The document is dated January 12, 1780 and virtually proves that Mrs. Windslow got the date of 1729 wrong in her book.

Figure 7: 1790 U.S. Census portion showing “Thatch” residents of Perquimans County, North Carolina. Source: Ancestry.com. 1790 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

John’s estate papers in the North Carolina State Archives reveal a great deal. Executors made inventory of his belongings in July 1779 and they showed the trappings of a moderately wealthy gentleman. He had four beds, three guns, a sword, old trunks, and looking glass (lending a bit of idiomatic maritime flavor). He owned also three slaves, a parcel of books, wooling and spinning wheels, weights for a scale, tar-rendering supplies, bee stocks, eleven head of cattle, assorted “Dunghill fowl,” turkeys, a cart, horses, and two pages of assorted household goods. He made his own tar to sell, honey, clothing, a large farm, and sold goods from his home.[23]

John’s son, Thomas Thach died about a decade after his father and he left estate papers showing the typical North Carolina family of the period. His inventory in 1792 showed two feathered beds, chairs, chairs, tables, and the usual household goods. As for Thomas’ work, he apparently had a small farm, basic iron tools including a plough, one gun, one slave named Jim to help him work the fields, three horses, two sows, nine pigs, ten shoats, and four old casks, indicating that he may have shipped some of his produce to nearby Edenton or Hertford. He was not rich, but neither was he poor for the times. He owned a horse cart, extra wheels, and a canoe for short trips down Indian Creek, which flowed west into the Chowan River north of Edenton. His wife Mary Harmon Thach owned two spinning wheels, a loom, a pair of cards, and assorted pewter kitchen ware. She apparently made clothing for the family. Thomas’ son Nathan was executor to his father’s will.[24]

The given names of Spencer and Le[a]ven raise suspicions as possible Jamaican family names coming from Capt. Thache’s neighbors on that island, especially since these given names do not appear as common surnames in Perquimans County. Furthermore, searches on all databases for these specific individuals turn up no results in any other part of the world except Perquiman’s County, with only one early exception. They also follow the naming pattern established by the Jamaican Thaches in regard to Cox Thache, probably named for St. Catherine’s assemblyman Thomas Cox. John and Phyllis Spencer of St. Catherine’s Parish had their children: Elizabeth, William, Sarah, John, Thomas, Mary, and Henry between 1679 and 1695. They likely knew the Thaches of the same parish. The Levens family lived in the nearby Kingston parish where Edward Thache and his brother Cox once lived. Sarah Levins dies in 1697 in St. Andrew and Joseph Levens appears in 1738 in nearby Kingston. Then, there appeared ten Spencer children from St. Catherine’s Parish alone born between 1680 and 1720.[25]

The notable exception outside of Perquimans County is for Spencer “Thatch,” who appeared once in Gloucester County, Virginia when his daughter Mary marries Dr. James Boyd in 1726. The idea that this Spencer may equate the gentlemanly lineage of Thache’s family by marrying a physician seems possible, given the Jamaican records detailed for Capt. Thache’s family in chapter four [of Quest for Blackbeard]. This apparently gentleman “Spencer Thatch” in Virginia is a mystery, with no known origin. Using these data, Spencer should have been born before 1692 (average 16-year-old Mary at marriage plus Spencer’s age of 18 at her birth), probably earlier – generationally contemporary with Edward Thache. This Spencer Thach in Virginia is the right age to be John Thach of Perquimans’ father and some of his known connections (near the time of his arrival in Chowan, John was guardian to the heirs of Virginian Thomas Holliday) demonstrate a possible previous connection to lower Virginia. Furthermore, a suit brought against “John Thach” in 1745 appeared in Stratton Major Parish near Gloucester County. The supposition that this Thach family in Perquimans descended from the same Spencer Thatch whose daughter married Dr. Boyd in nearby Gloucester County, Virginia, merely a short trip north by water from the Albemarle, is quite good. If the elder Spencer was from Jamaica, then he was probably Edward Thache’s brother, perhaps another, unknown younger son of Capt. Edward and Elizabeth – however, assuming a birth on Jamaica, his disappearance from christening records cannot be easily explained. There was another possibility as well, Capt. Edward’s brother Phillip Thache may have accompanied his brother Edward and family from Bristol to Jamaica and Spencer could be his son. Still, with this scenario, we are left with similar problems, for where is Phillips’ burial record, assuming that he died young on Jamaica as did Capt. Edward’s first wife? Anglican Church records there were fairly well done and fairly comprehensive – but, there were mistakes. Perhaps he died at sea and was not buried? Moreover, why did the name “Phillip” not become perpetuated in Perquiman’s as with Spencer, Leven, and Thomas? Then again, a “Thomas Thatch (also spelled Thach)” appears in early records of Barbados when he witnessed the will of Elizabeth Goaring in 1693. Perhaps Phillip or Spencer may have gone there instead.[26]

Thomas is a common given name in the likely family of Edward “Blackbeard” Thache. His father, Capt. Edward Thache of Spanish Town was probably the son of Rev. Thomas Thache of Gloucestershire. Blackbeard’s half-brother, Thomas Theach/Thache, born November 17, 1705 was the only male child of Edward and Lucretia Theach who did not appear in future records of St. Catherine’s Parish in Spanish Town, Jamaica. He died in Middlesex County, England in 1748.

“Cox Thach” does not appear in Perquimans County records as do Spencer and Leven, but then again, at least one brother of Edward Thache Jr. remained in Jamaica as “Captain of the Train of Artillery,” as told by Charles Leslie. Another may have gone to Perquimans. Furthermore, Kingston records first began in the 1720s and nearby Port Royal Parish was unable to record any records because of the earthquake of 1692 and the damage to their church, St. Peter’s. The fire and hurricane ten years after prevented a rebuild. Records began again with a new church in 1725, after Spencer and any others might have been born. Their records were possibly lost. These Perquimans County, North Carolina Thaches may owe their anonymity to another disaster like those that may have hidden Thache and his sister’s births in Bristol. Many unknown possibilities still exist for Thaches born or who might have lived in Port Royal or Kingston at this time, even the possible family of Edward Thache Jr.’s uncle, Phillip Thach.[27]

Furthermore, the Thach given names do not appear to come from Perquimans County families, where Spencers and Levens did not live. “Spence” does, but this fails to explain the early “Spencer Thatch” in Gloucester County, Virginia records. Furthermore, Mrs. Winslow only mentioned one other man with that given name, Spencer Williams, beginning in 1770. The question is: Where did these Thaches come from? They are not recorded as born in England or any other part of America or the world, as evidenced by world-wide searches on Ancestry.com and Familysearch.org. Could they be from the islands of the West Indies? If they are from Jamaica, where only one Thache family lived, then they quite likely belong to the family of Blackbeard the Pirate. This still seems to be a good possibility, as circumstantial as the evidence may be.

Mrs. Winslow inferred that some “said that [Blackbeard] has descendants still living in the district but the writer does not give much credence to the fact.”[28] Even though almost everyone desires an “Indian princess” in their family, perhaps she had not looked in the local phone directory. Today, many Thaches appear in northeastern North Carolina, three in the Perquimans County seat of Hertford. Furthermore, nineteen people by that name are buried in the local graveyard. These results came from only a search in the county seat of Hertford. There are likely a great deal more in the surrounding county. Perhaps she only believed that the Thaches of Perquimans could not be related to the man who sailed from Bath Town for a brief time in his career. Despite Mrs. Winslow’s mistakes and her assurances to the contrary, Blackbeard’s descendants and/or descendants of his kin probably still live in the old Albemarle region of Perquiman’s County, North Carolina. The Albemarle was, of course, the original hiding place for “Pyrats and runaway Servants” as told by Edward Randolph, certainly upset about North Carolinians’ mistreatment of the Swift Advice-boat in 1698. [29]

Another possible family connection to the Pratts adds even more circumstantial yarns to the theory. Dr. Axtell’s son and maybe Lucretia’s brother-in-law, Daniel Axtell, cousin of the South Carolina landgrave and Lords Proprietor deputy of John Archdale, took his father’s place as an assemblyman. He was suspected of being “correspondents with and accessorys to pirates and piracys” in Jamaica in December 1716.[30] Their grandfather, Daniel Axtell was the infamous Member of Parliament that voted with other regicides to behead Charles I.

Most interesting in this regard is the will of Cox Thache in 1736 that mentions only two bequeathals: one to “Ann Smith” and the other to his absent brother Thomas. This “Ann Smith” was born Anne Pratt and married Richard Smith in 1714. She was to receive “The Table in the Hall being her own Purchase.”[31] The supposition that Lucretia was, at one time, the daughter-in-law of Dr. William Axtell of Port Royal and the sister-in-law of William Axtell of St. Catherine’s gathers ever more substance because of Dr. William Axtell’s marriage to “Sarah Pyott [often spelled “Pratt”].” Furthermore, Thankful Pratt, daughter of William Pratt of Massachusetts, married Daniel Axtell, a son of William and grandson of Thomas Axtell, brother of regicide Col. Daniel Axtell. These same Massachusetts Pratts and Axtells have lived variously in Massachusetts and South Carolina. As reminisced by Veazie Winthrop O'Hara some time in the 1940s or 50s upon his ancestors:

Some families or individuals returned to England, such as Thomas' brother Nathaniel Axtell, who started back from Conn. but died at Boston in 1640. Others tried life in So. Carolina, like the Pratts, Gobels, and Dillys, but returned to Mass. or N. J., many removed to N. J. from New England. - Typical is that of Daniel Axtell, who possibly accompanied Elder William Pratt from Mass. to So. Carolina, married his daughter, Thankful Pratt there, had their first children in S.C. but returned to Mass. where they raised a large family. After Daniel died in 1735 his widow and children removed to Mendham Township., Morris Co., N.J.[32]

Thaches, Axtells, and Pratts, as related families, appear to be inseparable. They are found together in Jamaica, Massachusetts and the Carolinas.

Mrs. Winslow told that the land for an Episcopal Church was donated by Elizabeth Mathias, wife of John and daughter of miller Jeremiah Pratt on July 17, 1732, “To the Parish of Perquimans ½ acre square of land for the Worship called the Church of England by Yawpim Creek bridge where a Chapple is now built, land formerly belonging to my father, Jeremiah Pratt.”[33] The fascinating connection here is for John Thach’s daughter Mildred, who probably married Job Mathias, son of John Mathias and his wife Elizabeth Mathias, the couple that donated the land for Yeopim Creek Church.[34]

Again, like in North Carolina, Jamaica’s privateers, and later pirates, came from their residents. John Augur, one of the pirates who had surrendered to Rogers with Hornigold, can be found mentioned in Johnson-Mist’s A General History. Supposedly, he accepted a pardon from Rogers only to “go on the account” again. Johnson-Mist says that he was captured and taken to New Providence for trial and there hanged with ten others. Kingston’s abundant burial records starting in 1722, however, show one “John Augier” among the seven persons buried on November 5th of that year who died in that sickly early port town. William Tyndall, a planter of Kingston had three children by Mary Augier (a free mulatto): Mary in 1724, Jenny in 1729, and William in 1732. Tyndall owned Jane, the slave that Cox Teach common-law married and the mother of Cox’s children, including the daughter, Lucretia, born in 1722. Other Kingston residents had common liaisons with Augiers: John Muir and Frances Augier in 1729, Samuel Spencer and Frances Augier in 1736, Theofihilus Blichendon and Jenny Augier in 1729, John Decumming and Jane Augier in 1733, 1737, and 1747, Gibson Dabzell and Susan Augier in 1729 and 1742, John Mahoney and Abigail Augier in 1748, and John Morse and Elizabeth Augier (aka, Tyndall) also in 1748. All of these Augier children were born out of wedlock, as Cox Thache’s children and some were associated with William Tyndall, as well. There was even a “John Teach” buried in Kingston in 1730, a decade before John Thach of Chowan and Perquimans County appears in North Carolina.[35]

The argument necessarily remains tenuous and circumstantial, but the chances are better than average. The Thaches of Perquiman’s County, North Carolina are probably from Jamaica, or at least the West Indies. They are also probably related to their neighbors, the Pratts. Furthermore, given the truth of that premise, then the probability that they were also related to Capt. Edward Thache of St. Jago de la Vega, Jamaica is good.

Lucretia’s probable ex-father-in-law, Dr. William Axtell of Port Royal, son of the regicide, died in 1723 and left a will wherein both of his sons William and Daniel were left significant estates in St. Andrew, Holborn, Middlesex, London. Both of his sons moved to London after his death. Daniel, who, like Tobias Knight of North Carolina, helped to fence and store pirated merchandise in Port Royal with Jasper Ashworth, married in 1725 and had several children during the next decade. He and William fought court battles over their London estates with their father’s executor Edward Fenwick. None of these records ever mentioned Lucretia’s name. Still, the name “Lucretia Theach of Spanish Town, Jamaica,” likely step-mother of Blackbeard the Pirate may have attracted some unwanted attention on court documents. “Axtell,” by itself, did not raise many eyebrows by the early eighteenth century; still, Lucretia’s step-grandfather helped to kill a king. Again, “treason” is as ambiguous as piracy - especially in America![36]

----------------------

[1] Ibid.

[2] “America and West Indies: August 1718,” Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies, Volume 30: 1717-1718 (1930), pp. 327-343, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=74045&strquery=spotswood 1718 (accessed: 30 November 2014).

[3] Rediker, Villains, 36.

[4] Butler, Pirates and Rebel Raiders, 39.

[5] Rediker, Villains, 45.

[6] Jane Stubbs Bailey, Allen Hart Norris, and John H. Oden, III, “Legends of Black Beard and his Ties to Bath Town: A Study of Historical Events Using Genealogical Methodology,” Beaufort County Deed Book I, 137.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Edward Salter, “Will of Edward Salter” (6 January 1734 – 5 February 1734), North Carolina Division of Archives (Raleigh: State of North Carolina).

[9] George Davis quoted in Hill, “Edward Moseley: Character Sketch”, North Carolina Booklet, 202; Herbert R. Paschal, Jr., A History of Colonial Bath (Raleigh: Edwards and Broughton Company, 1955), 32.

[10] Baylus C. Brooks, Dethroning the Kings of Cape Fear: Consequences of Edward Moseley’s Surveys (Greenville: Baylus C. Brooks, 2010).

[11] Bailey, Norris, and Oden, “Legends of Blackbeard.”

[12] Great Britain, Parliament, “Act of the Parliament of Great Britain to surrender the Lords Proprietors of Carolina's shares of Carolina to the Crown” (1729), NCCR, 3: 32-47; Encyclopedia of North Carolina , Vol 3, 2nd edition (St. Claire Shores, MI: Somerset Publishers, Inc., 1999), 56.

[13] Johnson, General History, 2nd ed., 76.

[14] John Teach (d. 1730), Mary Teach, and Lucretia Theach (b. ca 1722, ch. 1747). Lucretia Teach was born the year of yet another hurricane that struck just south of Port Royal, creating 14-16 foot wave surges. This storm accompanied record-keeping in the new parish. The first baptism recorded in Kingston Parish was for Smart May, the wife of the new minister, Rev. William May. She was “killed in the storm August 28th” 1722.

[15] Ellen Goode Rawlings Winslow, History of Perquimans County (Baltimore: Regional Publishing Co., 1974), 22-23.

[16] Ibid., 24-25.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ellen Goode Rawlings Winslow, History of Perquimans County (Baltimore: Regional Publishing Co., 1974), 22, 258, 270-271, 284.

[19] Ibid., 172; State of North Carolina, An Index to Marriage Bonds Filed in the North Carolina State Archives (Raleigh: North Carolina Division of Archives and History, 1977), 1: 39; “Will of Edward Hall” (probate: 28 Jan 1788), Perquimans County Wills, Vol C, 1761-1794; J.R.B. Hathaway, ed., “Abstracts of Wills of Perquimans County,” North Carolina Historical and Genealogical Register, Vol 3: 2 (April 1903), 173; William S. Powell, ed., Dictionary of North Carolina Biography: Vol. 3, H-K (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 6; Colonial Court Records, Taxes & Accounts, 1679-1754, CCR 190, Tax Lists, Perquimans County, 1702-1754, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh.

[20] Wynette Haun, ed., Chowan County Deed Book A-1, Vol. 1, 1741-1745 (DB: A-1: 350), 60; “George Mathews” and “Jeremiah Prat,” Patent bk. 1: 73, 3: 11, Secretary of State Patent Records, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh; Note 1: The location of the Pratt’s land is given in deeds variously as “Indian Creek” and “Yeopim Creek,” with an erroneous assumption that they connect. The actual location is best defined on Moseley’s Map of 1733 as “Sturgeon’s Point,” although the waterways are only roughly defined. Moseley also indicates the mill and the chapel of the Pratt’s. The chapel is actually within the boundaries of Chowan County, while the mill was just north of the church in Perquimans. Note 2: Mildred Thach Mathias shown on John Thach’s estate probably married Job Mathias (process of elimination). Job and Mildred are difficult to trace and disappear after Mildred’s father’s estate in 1779/1780. Mathiases appear in Gates County, founded 1779 only a few miles north of the Thach family location in Perquimans. Gates County Tax List for 1784 contains similar information to that given for the Thaches by Mrs. Winslow and called the “1729 Tax List.” Her information in 1931 may have come from a now lost similar tax list for Perquimans County, say in 1779 or 1789 – 1787 is the only year that is still extant. Likewise, Mary Thach might have married one of three sons of Ralph and Charity Doe. “Jeremiah” is given on the same erroneous tax list of Mrs. Winslow’s and also as Jeremiah “Dough” on the 1790 census. He is the youngest of Jacob (b. 1736), James (b. 1741), and Jeremiah (b. 1745), all in the right age range to have been married to Mildred Thach (from: The North Carolina Historical and Genealogical Register, Volume 3). Ann “Theach” m. Abraham Riddick in Perquimans County 12 Apr 1758 and is probably another daughter of John and Mildred Thach.

[21] “Martha Ann Kippen to John Thach” (1758), DB F: #287; “Benjamin Scarborough to John Thach” (1763), DB G: #69, Chowan County, North Carolina Deed Records (microfilm),

[22] "North Carolina, Marriages, 1759-1979," index, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/F8TJ-B4Q: accessed 07 Sep 2014), Jno Thach and Sarah Standin, 27 Apr 1748; citing Chowan, North Carolina, reference; FHL microfilm 6330322; "North Carolina, Probate Records, 1735-1970," images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/DGS-004770575_00311?cc=1867501&wc=MDRZ-43D:169835001,169912001 : accessed 15 Nov 2014), Perquimans > Estates, 1741-1804, Vol. T-W > image 38-40 of 215; county courthouses, North Carolina.

[23] “Estate Papers of John Thach of Perquimans County (d. 1779),” Familysearch.org.

[24] Thomas Thach (d. 1791), Wills and Estate Papers (Perquimans County), 1663-1978; North Carolina. Division of Archives and History (Raleigh, North Carolina), accessed through Ancestry.com.

[25] Scottish Record Office Class GD 1/26 No. 60, Penkill Manuscripts, Class GD 1/26 No. 60. (1726), at Library of Virginia, Virginia Colonial Records Project, Survey Report No. 8628 (accessed 14 January 2015); Old New Kent County [Virginia]: Some Account of the Planters, Plantations, and Places, Volume 1 (Baltimore: Geneaological Publishing Company, 2006), 367; "Jamaica Church of England Parish Register Transcripts, 1664-1880," index and images, FamilySearch, Rosanna Green, 21 Jul 1677, Christening; citing St Catherine, Sarah Levin, Burial, citing p. 267, St. Andrew, and Joseph Levens in entry for Elizabeth Harvey Levens, 21 May 1738, Christening; citing p. 50, Kingston, Jamaica, Registrar General's Department, Spanish Town; FHL microfilm 1291724.

[26] Ancestry.com, North Carolina, Marriage Index, 1741-2004 and English Settlers in Barbados, 1637-1800 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007), http://ancestry.com (accessed: 6 Sep 2014); Note that many genealogoies given for the Thaches of Perquimans show that Green Thach married Elizabeth “Spencer” and this is used to explain the name of his son, Spencer Thach. No known record, however, can be found to confirm her last name and this is assumed to be a guess made by an earlier genealogist. Moreover, another son is named Leaven. The naming of these two sons in a Thach family suggests a Jamaican connection in the absence of any other.

[27] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Baptisms, marriages, burials 1669-1764, Vols. 1 & 2,” Jamaica Church of England Parish Register Transcripts, 1664-1880 (Intellectual Reserve, Inc., 2014), https://familysearch.org/ (accessed 16 August 2014); Charles Leslie, A New History of Jamaica, from the Earliest Accounts, to the Taking of Porto Bello by Vice-Admiral Vernon. In thirteen letters from a gentleman to his friend…. (London: printed for J. Hodges, at the Looking-Glass on London-Bridge, 1740), 91.

[28] Winslow, History of Perquimans County, 25.

[29] David Stick, The Outer Banks of North Carolina 1584-1958 (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1958), 23; Whitepages Search online for “Thach” in Hertford, North Carolina,” http://www.whitepages.com/name/thach/Hertford-North-Carolina (search performed 15 Nov 2014); Find-a-grave search for “Thach” in “Hertford, North Carolina,” http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gsr&GSln=Thach&GSiman=1&GScnty=1722& (searched 15 Nov 2014).

[30] “America and West Indies: December 1716, 1-15,” Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies, Volume 29: 1716-1717 (1930), pp. 211-232; "Jamaica Church of England Parish Register Transcripts, 1664-1880," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/VHDC-77R : accessed 02 Sep 2014), William Axtell & Sarah Pyott [Pratt], 5 Nov 1678, Marriage; citing p. 177, St. Catherine, Jamaica, Registrar General's Department, Spanish Town; FHL microfilm 1291698; Axtell-Pyott [Pratt] marriage in correct range to be her parents (1678).

[31] “Will of Cox Thache” (1736).

[32] Veazie Winthrop O'Hara, “Into the Wilderness,” Axtell - Condit - Dilley and our Allied Ancestors [online], http://www.pitzer-legacy.com/IntoTheWilderness/Index.html (accessed 5 January 2015).

[33] Ibid., 37.

[34] Winslow, History of Perquiman, 34.

[35] Johnson, General History, 2nd ed., 37; "Jamaica Church of England Parish Register Transcripts, 1664-1880," FamilySearch.org, Mary Augier in entry for Jenny Tyndall, 16 Jul 1729, Jenny Augier in entry for Sharlott Blichandon, 16 Jul 1729, Susanna Augier in entry for Frances Dalzell, 18 Jul 1729, Christening; citing p. 19, Susan Augier in entry for Robert Dalzell, 08 Nov 1742, Christening; citing p. 70, Mary Augier in entry for Mary Tyndell, 06 Aug 1724, Christening; citing p. 5, Frances Augier in entry for John Muir, 13 Apr 1732, Christening; citing p. 29, Frances Augier in entry for Hannah Spencer, 05 Mar 1736, Christening; citing p. 45, Jane Augier in entry for Edward James Decumming, 13 Nov 1733, Christening; citing p. 34, Jane Augier in entry for Dorothy Decumming, 07 Nov 1737, Christening; citing p. 48, Jane Augier in entry for Peter Ducommun, 05 Apr 1747, Christening; citing p. 91, Elizabeth Augier Or Tyndall in entry for Sarah Charlotte Morse, 07 Mar 1748, Christening; citing p. 99, Abigal Augier in entry for Mary Mahony, 27 Jan 1748, Christening; citing p. 98, Kingston > Burials 1722-1774, Vol. 1 > image 3 of 245, Kingston, Jamaica, Registrar General's Department, Spanish Town; FHL microfilm 1291763.

[36] National Archives, KEW, C 11/2270/10, Axtell v. Axtell (1735), Court of Chancery: Six Clerks Office: Pleadings 1714 to 1758.

---------------------------------------------------------

Read about North Carolina's piratical birthpangs in the Brunswick Town & Wilmington affair and the hero that saved the Port of Wilmington from the Family's political opposition, Capt. James Wimble:

Both can be found at the author's Amazon page and at Lulu.com

From the author of Blackbeard Reconsidered!