They also built a full fort there that very much resembles the Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine, Florida. And, Fort of San Miguel also still stands!

"Ah Kim Pech," or "Cam Pech," the site of future Campeche City was originally an indigenous village, called "Calakmul" by the Mayans, where the Spanish first landed in Mexico in 1517. It boasted a population of 50,000 at its height in the 6th and 7th centuries A.D. The Pre-Columbian city was described as having 6,000 houses and other structures. San Francisco de Campeche was founded there in 1540 by Francisco Montejo, Merida in 1542, along with 30 monasteries throughout the region. As a vulnerable port, Campeche was systematically terrorized by pirates and marauders until the city started fortification in 1686.

An eminent example of the military architecture of the 17th and 18th centuries, Fort of San Miguel is part of an overall defensive system set up by the Spanish at Vera Cruz to protect the ports on the Gulf of Mexico from pirate attacks like the infamous English 1663 Sack of Campeche.

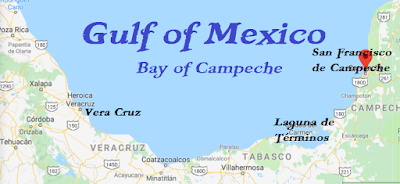

Laying roughly 65 miles SW of Campeche lay the Laguna de Términos and it's associated Isla Del Carmen (formerly known as Isla Triste) which had finally been liberated from English pirates on July 16, 1717. Another 250 miles away - across the Bay of Campeche in the southern Gulf of Mexico - lay Vera Cruz, the capital of New Spain's province of Mexico.

|

| Fort of San Miguel, San Francisco de Campeche |

|

| A local beach on the shores of San Francisco de Campeche, Mexico - shows the Bay of Campeche in the Gulf of Mexico |

Hubert Howe Bancroft, in his History of Mexico, Vol. XI told of the struggles that Campeche had incurred due to the English, French, and Dutch pirates of the 17th century. Since 1632, these foreign buccaneers attacked all of New Spain, but Campeche had been especially troublesome for viceroys of New Spain at Vera Cruz. He wrote:

In 1632 six vessels threatened Campeche, but timely succor made them retreat. In August of the following year the town was again visited, this time by ten vessels under a leader known to the Spaniards as Pie de Palo. Guided by a renegade, he advanced against the entrenchment behind which Captain Gal van Romero had retired, but a well directed fire killed several of his men, and caused the rest to waver. It would not answer to lose many lives for so poor a place, and so a ruse was resorted to. The corsairs turned in pretended flight. The hot-headed Spaniards at once came forth in pursuit, only to be trapped and killed. Those who escaped made a stand in the plaza, whence they were quickly driven, and thereupon the sacking parties overran the town. Seven years later Sisal was visited by a fleet of eleven vessels and partly burned after yielding but little to the raiders.

In the following year they returned under the command of their two famous leaders Pie de Palo and Diego the Mulatto. After a hot fight the town was taken and sacked. Efforts to obtain a ransom failed, however, and when rumors of a force approaching from Merida became known to the corsairs, they departed.In April 1648 these same pirates captured a frigate with more than a hundred thousand pesos on board, and a few weeks later boldly attacked a vessel in the very port of Campeche. At about the same time another band, commanded by the Dutch pirate Abraham Blauvelt, captured Salamanca.

During the second half of the seventeenth century pirate raids became more frequent. In 1659, 1663, and 1678 Campeche was again taken and sacked by English and French freebooters. "They were aided on this occasion by logwood-cutters, who since that time had begun to establish themselves on the peninsula; and, notwithstanding the repeated efforts of the Spaniards to expel them, successfully maintained their positions, till in 1680 they were driven from the bay of Terminos by forces sent against them from Mexico and Yucatan."

This raid of 1663 was particularly devastating. Christopher Myngs and Edward Mansvelt led an expedition of 14 vessels from Jamaica with 1400 men to raid the Spanish town and establish themselves at the Laguna de Términos. They were joined by four more French vessels and three Dutch for a total force of 20 vessels. It was an all-out invasion of Mexico by other squatter nations in Spanish America! But, the English were the primary aggressors in this action. Like most walls in history - especially those in the modern day - the wall around Campeche was wholly ineffective against English pirates!

Eva Leticia Brito Benítez, in "Pirate Assaults and the Defense of the Old Seaport of Campeche, Mexico (16Th-18Th Centuries)," Journal of Global and Area Studies writes:

In the same year, a raid of pirates burned lands but Captain Maldonado, commanding 200 soldiers and 600 Indian archers, forced them to retreat. Several criminals were captured and sentenced to death, among them was a man called Bartolomé Portuguese and known for having previously escaped Campeche.In 1669, Spanish slaves rose up and decimated Campeche, and in 1670s Campeche was continually set upon by English pirates, who enjoyed protection from Gov. Thomas Lynch of Jamaica. English corsair Lewis Scott assaulted the village in 1678 and according to witness’s testimonies, he kidnapped 250 families. He also stole a lot of gold, silver, jewelry, sacred ornaments, sugar, soap, and meat; additionally, he took three of the fortress’s flags, broke down all of the artillery, and drilled 150 muskets. The garrison consisted of but two companies of half-clad and poorly fed soldiers, until after the raids of Scott and Lorencillo in 1678, when two more companies were sent from Spain.

In 1680, English and French logwood pirates, were expelled from the Laguna de Términos and in 1690, the Spanish fortified Isla Triste or today’s Carmen Island with artillery. A serious effort was made to defend the lagoon or bay, for the garrisons at Campeche were "constantly threatened by the wood-cutters of the bay of Terminos," as Bancroft inferred.

In San Francisco de Campeche, up the coast, the project of Martin de la Torre, begun in 1680, was passed to the French engineer Louis Bouchard de Becou. It was commissioned to unify all the defensive works that surrounded the city with a wall against the incessant English attacks from Jamaica. At its completion, the wall was 2,560 meters in length, forming an irregular hexagon around the main part of the city, with eight defensive bastions on the corners. Bancroft wrote "The total cost of the fortification of Campeche, derived from contributions by the crown and the inhabitants, and from certain imposts, amounted to more than 200,000 pesos. In February, 1690, the first pieces of heavy artillery ever seen in the province were landed at the town." The fortress was completed by 1710. Much of these walls still exist.

|

| Project of Martin de la Torre - 1680 |

|

| Mapa-histórico-de-Campeche-la-Muralla |

|

| Modern city of San Francisco de Campeche |

Wood-cutters returned to Laguna de Términos in two years, but Viceroy Conde de Galve reinforced the garrison there and repelled them again. Like the “place of snakes and ticks” of "Cam Pech's" name, the pirate pests returned again and again, persistent as ever.

|

| Location of Isla Triste or Isla Del Carmen or Carmen Island. |

About the pirate encampment, Bancroft wrote that a favorite rendezvous of these adventurers was the Isla Triste, or as it is now known the Isla del Carmen, at the entrance of the bay of Terminos. This base made for a perfect launching point and outpost to watch for and chase the Treasure Fleet carrying gold and silver back to Spain. During the war of the Spanish succession they frequently attacked Spanish vessels trading between Campeche and Vera Cruz. When pirates again became a nuisance after the Hurricane of 1715, another minor attempt to clear them was made in 1716, [but again, like the pests that Spaniards had always perceived them to be,] they returned. The new Viceroy in Vera Cruz, Baltasar de Zúñiga y Guzmán, 1st Duke of Arión, 2nd Marquess of Valero, then launched

... an expedition… despatched from Mexico by way of Vera Cruz to Campeche, and being reinforced by the troops stationed there, drove the intruders from all their settlements on the bay of Terminos. The attack was made on the 16th of July 1717, the feast of the virgin of Carmen, and hence the island [formerly Triste] received its name.

Bancroft continued:

A large amount of booty was wrested from the buccaneers, many of whom were slain, those who escaped harboring in Belize [in Bay of Honduras], where, being joined by others of their craft, they organized a force of three hundred and thirty-five men and returned to the bay of Terminos. Landing on the Isla del Carmen they sent a message to Alonso Felipe de Andrade, the commander of the Spanish fort which had been erected during their absence, ordering him to withdraw his garrison. The reply was that the Spaniards had plenty of powder and ball with which to defend themselves. The freebooters made their attack during the same night and captured the stronghold without difficulty, taking three of the four field pieces with which it was defended. But Andrade was a brave and capable officer, and his men were no dandy warriors. Placing himself at the head of his command he led them against the enemy, forced his way into the fort, recaptured one of the field pieces, and turned it against the foe. During the fight a building filled with straw was set on fire by a hand grenade. This incident favored the Spaniards, who now made a furious charge on the invaders. Their commander was shot dead while leading on his men; but exasperated by the loss of their gallant leader, they sprang at the buccaneers with so fierce a rush that the latter were driven back.

Contrary to this historical rendering, Adam Anderson of the British South Sea Company wrote of unwarranted English problems with the Spanish, asserting that the English had every right to cut logwood (a valuable source of die) from the area of Campeche surrounding the Laguna de Términos... a location that included the Isla Triste, a frequent settlement of "British subjects." He titled his treatise "The Right of British Subjects to Cut Logwood at the Bay of Campeachy, Fully Stated" (1717).

Before the massive raid, in 1716, the Marques de Monteleone delivered a memorial to the "British subjects" - as Anderson referred to these moral-less merchants and brigandish boatmen - at the Isle of Triste "That, if, in the space of eight months, they did not leave the said place, they shall be considered and treated as pirates." This pronouncement alarmed the South Sea Company's Anderson, who believed it of vital importance to his company's business to state firmly (read: propagandize) British rights to the land at Términos - land that they had basically squatted upon and were run off from repeatedly for more than 50 years - although Anderson never mentioned that detail!

Anderson did admit that the English - he didn't say "pirates" - had taken the Spanish port of San Francisco de Campeche three times in recent history - though they never occupied it. He basically argued that the port and inland towns of Merdida and Valladolid were "in a manner, wholly desolate and uninhabited." Well, why would pirates go through the trouble of taking it three times, then?

The Yucatan region did become the slowest growing area in Mexico, but not until the turn of the 19th century. San Francisco de Campeche was a bustling and important port of New Spain in the early 18th century - not as important as the capital at Vera Cruz, of course - and currently boasts of more than 200,000 residents. The state of Campeche has almost 900,000. The entire state of Mexico contained approximately 5-5.5 million residents in 1810. It's doubtful that the region was as desolate as Anderson inferred - perhaps disingenuously.

Anderson said that the English at Laguna de Términos magnanimously allowed the Spanish to occasionally cut their own logwood "in several parts near their own settlements" from time to time. He asserted that "pirates" - not necessarily "English" pirates - were numerous before the Treaty of Madrid in 1667, when the Spanish gave them rights to Laguna de Términos.

Did the Spanish actually give them rights to Laguna de Términos?

The man who negotiated that treaty for England, Richard Fanshawe, was charged by his superiors to demand reparations for wrongs committed against English merchants and to point out Spain's impotency in the West Indies and to assert the superiority of England's maritime strength. Fanshawe was not achieving England's demands, even against a Spanish Empire inflicted with a weak ruler, King Phillip. England replaced Fanshawe with Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich.

Negotiations were inclined against Spain when Portugal and France signed a treaty in March 1667 and France agreed to support an invasion of weakened Spain. Sandwich simply revisited Fanshawe's original treaty with some variation - mostly that England was granted ‘most favoured nation status’ and particularly that England was allowed to carry into Spain her colonial products and goods bought by their agents on either side of the Cape of Good Hope. Although the treaty never mentioned Laguna de Términos by name, British merchants, companies, and their oft-associated pirates used this treaty as an excuse to lay claim to the area. Essentially, the treaty stated that they both promised not to navigate or trade in the places occupied by the other.

So, no, Adam... Spain did not give the English specific rights to Laguna de Términos.

What's worse for Spain is that Portugal suffered a coup the next year, essentially removing the greatest fear that caused her negotiators to allow such magnanimous concessions to England.

Still, Anderson said that "the British privateers [after the Treaty] were then induced to quit their former course," which is not really true, but the most narcissistic part came next... "and to settle with the Logwood cutters in Laguna de Terminos, so that in the year 1669, their numbers were considerably increased, and great quantities of wood were transported both to Jamaica and New England."

He argued that the Spanish never acted as though the English "cutting of logwood was then esteemed an invasion." Yet, still, booted them from the lagoon in 1680. Anderson simply did not acknowledge the English crossing the border into Spanish territory and stealing their logwood precisely constituted that "invasion." He only touted the great profits accrued by his company through their cutting logwood (stealing valuable merchandise) in Campeche.. and, of course, the boon to the entire British Empire. In a textbook example of sheer narcissism, Anderson expressed anger at the Mexican authorities for resenting this theft!!!

No wonder they were back at war in December of 1718.

Welcome to America - abode of pirates - those at sea and those in business suits! Nothing personal, of course.. just "friendly" competition. Just ask the pirates who razed San Francisco de Campeche, stole their slaves and Indians, and robbed and burned their citizens .

Reinforcing the "desolate" narrative, Anderson also told that Sir Thomas Lynch, then governor of Jamaica, had informed Secretary of State Earl of Arlington that their privateers had ventured seven or eight miles into the country although they "never saw any Spaniards!" And, that "our King's subjects [again, not "pirates"] have been used, for some years, to hunt, to fish, and to cut logwood, in divers bays, islands, and parts of the continent, not frequented or possessed by any of the subjects of his Catholic Majesty, and without any molestation." He also asserted that their activities were approved by the King's Privy Council.

Indeed, this piracy was approved by British authorities - since 1588! That was the problem. The ideology of harsh British capitalism-piracy created the United States. And, America has not changed.. only grown even more detached and "businesslike" - capitalists of the United States ideologically descended from the British South Sea Company - in its martial treatment of and capitalist trickery used against the Spanish.

The rhetoric used by Trump and Republicans today - of a wall against our friends - words like "animals" or "invasion" to describe immigrants at the Mexican border - is abominable in the extreme. Our Mexican friends in Campeche today only welcome us to their shores. Historically, from 1632 through today - for 387 years, we Anglo-Americans have climbed Spanish walls intended to keep us out - we raided, pillaged, and murdered these fine folks - rarely have we been good neighbors!

------------------------------------------------

Fountain of Hope: Dimensions

Available at Lulu.com

Epub version, too!

Also on Amazon.com!

BLACKBEARD: 300 YEARS OF FAKE NEWS.

from BBC Radio Bristol

300 years ago on Thursday - 22 November 1718 - Bristol born Edward Teach (aka Blackbeard, the most famous pirate in the history of the world), was killed in a violent battle off the coast of North America. And after 300 years we can finally separate the truth from the myth. You can hear the whole story this Thursday at 9am in a one off BBC Radio Bristol special: BLACKBEARD: 300 YEARS OF FAKE NEWS. With new research by Baylus C. Brooks, narrated by Bristol born Kevin McNally - Joshamee Gibbs in PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN, and produced by Tom Ryan and Sheila Hannon this is a very different Blackbeard from the one in the story books...

https://youtu.be/AnaYDaNoufE

No comments:

Post a Comment