Depositions are legal documents taken to investigate a legal matter. It's the same as an interrogation. That does not mean, however, each deposition and the person being deposed are trustworthy. Many criminals have lied to the police! There's no reason to suspect that any witness cannot be lying as well - maybe they want to keep their cousin out of jail! Depositions become matters of public record and will survive indefinitely. Lies can persevere as well as truth.

The task of the historian is to investigate the events mentioned in the deposition, who the deponent is, why are authorities engaged in this investigation, and what are the deponent's motivations for telling the authorities about the event. Yes, this is a lot of work. [Sarcasm alert:] That's why historians are paid the big bucks! 😂

Today, we take a look at the Deposition of John Vickers, enclosed in a letter to the Admiralty from Lt. Gov. Spotswood, dated 3 July 1716.

Where was this deposition taken? York County, Virginia. The governor then was Lt. Gov. Alexander Spotswood (because the actual governor George Hamilton did not think coming to America was necessary for his paycheck!) and he had much angst for pirates at this time. Williamsburg, Virginia was the capital of the Virginia Colony from 1699 to 1780. Presumably, the deposition was taken there - no specifics were mentioned as to location. British magistrates were in the habit of visiting deposers at their place of residence (whether a rental or home). So, the assumption is that the same occurred in Virginia with Thomas Nelson, the presumed interviewer and magistrate in this case. Thomas Nelson signed as witness to Vicker's deposition and no one else was mentioned in a magisterial context. A postscript is attached, mentioning Barbados merchant Alexander Stockdale (b. circa 1656), was taken by pirates and was with Vickers in Providence, Bahamas at the time of these events. He confirmed the veracity of Vicker's testimony and Nelson also witnessed his statement. This is an important point - a second person validated the deposition at the time the deposition was taken and was involved in the events in the deposition.

The date of 3 July 1716 is not the actual date of the deposition. It's the date of Spotswood's letter and he mentions in his letter that the enclosure is a duplicate from 28 May 1716. So, the actual deposition had to have occurred before that date. The events in the deposition span the period Nov 1715 - 22 Apr 1716, and accounting for the travel time from the Bahamas to Virginia, the deposition most likely occurred sometime in May 1716. Whether Vickers was present for all the events he testifies upon at Providence is not certain - only that he knew about them possibly from word of mouth from others, but it is reasonably certain that he was there for the conclusion of these events.

Now, who is John Vickers? My book Dictionary of Pyrate Biography was written partly to provide historians biographical information on key players related to piracy simply to provide context for such investigations. Thus, an entry on John Vickers - an important witness to pirate history - was included:

Vickers, John - from Bermuda, grandson of original wealthy immigrant (1635) Severin Vickers, had once served on the council of St. Christopher’s Island [St. Kitts] in the 1680s. His uncle Richard, in 1677, replaced Simon Musgrave as Customs agent for Jamaica. Then, John Sr. was appointed to the General Assembly of the Leeward Islands, on October 1, 1683. Perhaps it was his son who, a younger man in 1716, had been living on New Providence when the growing band of multinational rovers infested the island in the spring and summer of that year and caused him to leave for Virginia.

The young merchant Vickers, barely twenty, gave his deposition before Thomas Nelson, originally of Penrith, Scotland, then a twelve-year resident of Yorktown, Virginia with a son on the way (Thomas, Jr., a future governor of Virginia).

Vickers was a young man at the time he gave his testimony. Alexander Stockdale was 58 years old, yet Vickers was the one deposed. Spotswood's letter provides the context: Vickers was the man chosen by Spotswood to obtain this information. Did Spotswood think that a younger man might be more idealistic and less experienced in deception than an older man? Or, did Spotswood think that Vickers was impressionable and willing to curb his testimony to fit the desires of possibly pirate-hating Spotswood himself?

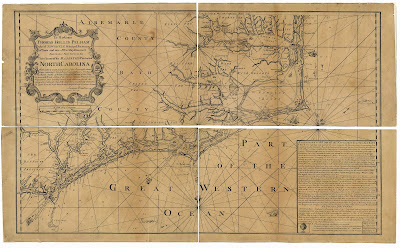

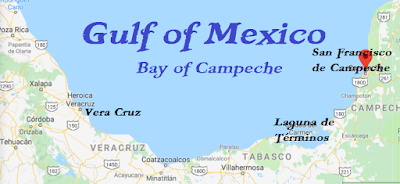

Reading Spotswood's letter gives clues as to his possible state of mind. He mentioned the dangers of a "Nest of Pirates" and that they could possibly grow by the addition of "loose disorderly people" from the logwood cutters at the Bay of Campeche on the Spanish mainland. This might have been professional concern, but his history and the later murder of Blackbeard in another colony seem extreme and may also indicate more than a professional pecuniary interest in rooting out pirates. Spotswood had recently dealt with Forbes and three others, pirates who wrecked upon Cape Hatteras (in North Carolina, BTW.. same place he went after Blackbeard) and were brought back to Virginia. They had since escaped. By this time, Spotswood had determined that the Proprietary government of northern Carolina was not trustworthy and he took upon himself the charge of policing their waters - as we later see with the expedition against Blackbeard in the Pamlico region. In May 1715, he also sent Capt. Harry Beverly on an expedition to Florida in Spanish territory to investigate Providence, but Beverly was caught in the Hurricane of 30 July 1715 which wrecked eleven Spanish treasure ships on the coast of Florida.

Spotswood perhaps showed a tendency toward obsession in these matters that did not directly pertain to the administration of his colony. Spotswood might have been aware of his precarious position and noted in his letter that his authority came through:

... having power by a Commission from His late Majesty King William under the Great Seal of Admiralty for the appointment of the Officers of the Admiralty in these Islands to make particular enquiry into the state thereof: and to that end have encouraged the Master of a Sloop bound from hence on a Trading Voyage to these parts [the Bahamas] to mann extraordinarily the Vessel under his Command, and endeavour to obtain the best account he can of the number Strength and design of those Pirates....

But, any colonial administrator could have claimed this authority. Beverly and Vickers were actually sent on a spy mission for Spotswood. Was Spotswood perhaps abusing his authority? One could argue that he was merely more attentive to his admiralty duty than most negligent colonial administrators. Still, Spotswood and Beverly repeatedly insisted that Spotswood had the authority. When you often officially voice your authority, there's at least a chance that you're not quite certain that you had authority! The old "where there's smoke" argument.

I know this seems quite critical, but that's the point, isn't it? Not all questions are answerable, but we must at least consider all possibilities and investigate what we can. Always ask questions! Again, this requires meticulous research - much easier and faster now in the computer age! But, veracity of the deposition should be established as well as possible before it is used to argue a point. The reputation of the historian is on the line with every conclusion he/she makes!

Finally, as to the deposition itself, we start with a timeline of the events mentioned (which originally appear somewhat out of chronological order). Placed in chronological order:

~ July 1715, Daniel Stillwell of Jamaica moved to the island of Eleuthera and went in a small shallop with John Kemp, Matthew Low, two Dutchmen, and [Jonathan] Darvill to Cuba stole 11,050 pieces of eight from a Spanish launch and took it back to Eleuthera.

Later, Capt. Thomas Walker of Providence heard about the theft from the governor of Jamaica and took Stillwell and his vessel into custody, but Benjamin Hornigold arrived at Providence and declared all pirates were under his protection. He then had Stillwell and his vessel released.

👉Nov 1715 - Benjamin Hornigold arrives at Providence with sloop "Mary of Jamaica, owner Augustine Golding," and another "Spanish sloop" to dispose of the goods. BCBNote: Vickers then said "but, the Spanish Sloop was taken from the said Hornigold by Captain Jennings of the Sloop Bathsheba of Jamaica." Afterward, Jennings supposedly stayed in the Bahamas until Mar 1716. There are errors in this part - possibly because Vickers may have been told about these events and may not have actually witnessed them.

Jan 1716 - Hornigold leaves Providence in "said sloop Mary" and captures another Spanish sloop off Florida. Hornigold fits out the Spanish sloop and sent Golding's "Mary" back to him.

~1 Mar 1716 - Capt. Fernandez of Jamaica in sloop Bennett took a Spanish sloop and robbed them of about "Three Millions of money" and split the shares at Providence, then went back to the north shore of Jamaica.

Mar 1716 - Hornigold leaves Providence in his new Floridian prize - the captured Spanish sloop.

👉Mar 1716 - Jennings departs Providence.

👉22 Apr 1716 - Jennings arrives at Providence with a French sloop taken at Bahia Honda on Cuban Coast. Jennings takes this sloop to the wrecks off Florida to fish for treasure.

Vickers then mentions there are about 50 men who deserted while fishing the wrecks and caused disorders at Providence.

He tells of Thomas Barrow, formerly mate of a Jamaican Brigantine, who stole money and goods from a Spanish Marquis - now wants to go pirating. Barrow claims to be governor of Providence and says that 5-600 more Jamaicans will join them to make war on French & Spanish, but will leave English vessels alone. But, Barrow later took a New England Brigantine in Providence Harbor and a Bermuda sloop, beat and confined its master Butler, then discharged the sloop.

It's also common for the sailors there, says Vickers, to extort money from the inhabitants. Stockdale was extorted as well, but then Barrow and Peter Parr gave Stockdale a receipt for the money he paid them.

These events were jotted down from memory, somewhat out of order. Moreover, Hornigold may indeed have arrived in Nov 1715 with a sloop named Mary, but having a sloop "Mary" stolen from him by Jennings did not happen until April 1716. Vickers confused these two events - Jennings arriving on 22 Apr 1716 is probably correct and the date when Jennings took back the French sloop - not Spanish. That's why I've marked it in colored text.

According to three other depositions about theft of two French sloops at Bahia Honda on the coast of Cuba, Jennings in Bathsheba and two other sloops had taken these ships in Apr 1716. They were Mary of Rochelle and Marianne. Hornigold and his men stole Mary of Rochelle from Jennings et al. Hornigold then took the ship back to Providence and Jennings followed him there. That could be the 22 Apt 1716 date given by Vickers - incidentally the month before he gave the deposition, so a recent event. The earlier date, however, of March 1716 for when Jennings left Providence may have been in error. These depositions can be found here, here, and here.

Henry Jennings followed Hornigold back to Providence that April 1716 and then took Mary of Rochelle back from him, leaving him with Marianne. This Marianne is the same one taken from Hornigold by Samuel Bellamy when they later parted company with Hornigold.

Yeah, my brain hurt when I researched this the first time. Persistence and thorough research was the key! Many researchers have confused these events and I believed they needed a thorough investigation to confirm them.

Vickers was a reasonably accurate reporter, but he had probably only heard some of Hornigold's deeds as hearsay in Providence bars (Nov 1715 data) and may have actually seen Jennings take Mary of Rochelle away from Hornigold in late April 1716 and assumed it was the same vessel Mary that belonged to Augustine Golding of Jamaica. An honest mistake, really....